The Global Gauntlet: Structuring Finance for Cross-Border M&A Deals

The siren song of cross-border M&A is irresistible for ambitious companies. It promises new markets, technological dominance, and economies of scale on a global stage. Yet, for every triumphant deal that reshapes an industry, countless others falter, not for a lack of strategic vision, but in the treacherous maze of financing. Structuring the payment for a domestic acquisition is a complex task. Structuring it across borders, with multiple currencies, tax codes, and regulatory bodies, transforms the exercise into a high-stakes, three-dimensional chess match. This article provides a rigorous framework for seasoned M&A professionals, offering a clear path through the complexities of structuring financing for global deals. We will explore the core challenges, dissect a three-pillar framework for creating robust financing structures, and examine real-world cases that bring these principles to life.

The Allure and the Agony of Going Global

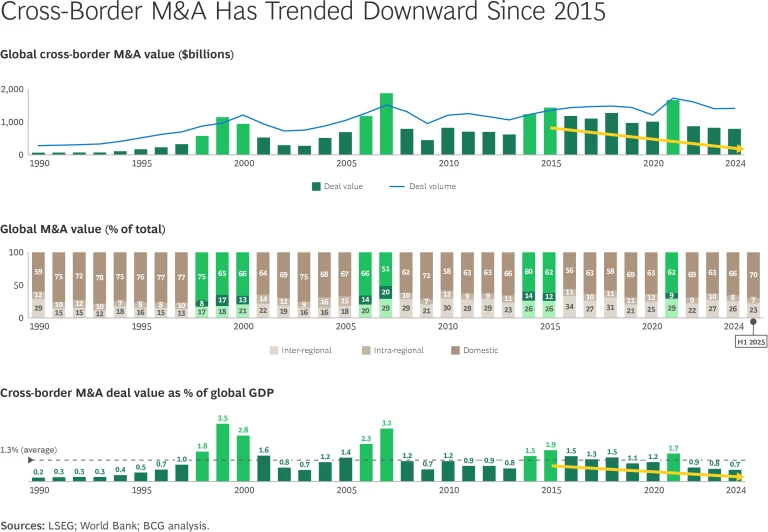

Embarking on a cross-border acquisition is a declaration of strategic intent. Companies pursue these deals to gain a foothold in new geographic markets, acquire unique technologies or talent, or create powerful synergies by combining operations across continents. The current global landscape, however, adds a fresh layer of complexity to this pursuit. We are witnessing a confluence of powerful trends that directly impacts deal financing. Geopolitical tensions can suddenly render a market inaccessible or a currency unstable. Heightened regulatory scrutiny from bodies like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and its counterparts worldwide means that the source and structure of financing are under a microscope. Furthermore, volatile currency exchange rates can turn a profitable deal into a loss-making venture overnight if not managed correctly. These elements make the modern cross-border deal environment both more challenging and more rewarding for those who can navigate it successfully.

Is It Really That Much Harder?

A straightforward question deserves a straightforward answer: yes, financing a cross-border deal is significantly more difficult than a domestic one. Finding the right financing structure for any deal involves balancing cost, risk, and control. For a cross-border transaction, this balancing act is performed on a high wire stretched between two different regulatory and economic worlds. The difficulties multiply exponentially. Acquirers must contend with disparate legal frameworks governing debt covenants and shareholder rights. They must navigate labyrinthine tax codes where a simple interest payment can trigger hefty withholding taxes. They face the ever-present risk of currency fluctuations eroding the value of their investment. The pool of lenders may be different, the required documentation can be duplicative and contradictory, and the timeline for securing commitments is often longer. The core challenge is not merely securing capital; it is about securing the right type of capital, in the right currency, from the right jurisdiction, and under terms that will not cripple the newly combined entity.

The Deal Architect’s Toolkit: A Framework

Architecting the Global Capital Stack

The first pillar of a successful cross-border financing structure is the thoughtful construction of the capital stack. This is the blend of equity and debt used to fund the purchase price. While the components are familiar, their application in a global context requires a nuanced approach. The goal is to optimize the cost of capital while respecting the legal and tax realities of each jurisdiction involved.

The primary components of the capital stack are:

- Senior Debt: This is the cheapest and most common form of financing, typically provided by banks and sitting at the top of the capital structure in terms of repayment priority. In a cross-border deal, a key question arises: should the debt be raised in the acquirer’s home currency, the target’s local currency, or a major global currency like the U.S. dollar? Raising debt in the target’s local currency can create a natural hedge if the target’s revenues are also in that currency. However, it may come at a higher interest rate or from a less-developed local credit market.

- Mezzanine Finance: This flexible layer of capital sits between senior debt and equity and includes instruments like subordinated debt or preferred equity. Mezzanine is more expensive than senior debt but less dilutive than pure equity. For cross-border deals, it can be an invaluable tool to bridge a valuation gap or to fund a portion of the deal when senior debt capacity in the target’s country is limited. Its structure (e.g., payment-in-kind interest) can also help ease cash flow pressures in the initial years post-acquisition, a crucial benefit when dealing with integration complexities.

- Equity: This represents the ownership stake and is the most expensive form of capital. It can come from the acquirer’s own balance sheet (cash on hand), the issuance of new shares to the public, or a direct issuance of stock to the target’s shareholders. Using stock as acquisition currency can be particularly attractive in cross-border deals. It aligns the interests of the target’s shareholders with the future success of the combined company and can mitigate some of the acquirer’s upfront cash burden. However, it also introduces complexities related to stock market regulations in different countries and potential flow-back, where the target’s former shareholders immediately sell the acquirer’s stock.

Solving the Jurisdictional Jigsaw

The second pillar addresses the critical question of where to house the acquisition vehicle and the associated debt. This is not a trivial administrative decision; it is a strategic choice with profound tax, legal, and operational implications. An improperly placed financing structure can lead to tax leakage, regulatory hurdles, and difficulties in repatriating cash.

The primary options for locating the financing are:

- Acquirer’s Home Country: This is often the simplest path. The company can leverage existing relationships with its domestic banks and operate under a familiar legal and tax system. However, this may not be the most efficient choice. Repatriating profits from the foreign target to the home country to service the debt can trigger withholding taxes and subject those earnings to a higher corporate tax rate.

- Target’s Home Country: Raising a portion of the financing in the target’s jurisdiction can be highly strategic. It can provide a natural currency hedge and may be looked upon favorably by local regulators. It also allows interest on the local debt to be deducted against the target’s local taxable income, creating a tax shield where it is most needed. The challenge lies in navigating an unfamiliar credit market and legal system.

- Neutral Third-Country Holding Company: This is the sophisticated M&A professional’s secret weapon. Establishing a holding company in a jurisdiction known for its favorable tax treaties and stable legal environment—such as the Netherlands, Luxembourg, or Ireland—can be incredibly efficient. These countries often have extensive tax treaty networks that can reduce or eliminate withholding taxes on dividends and interest payments flowing between the target, the holding company, and the ultimate parent company. This structure, often called a “Double Dutch” or similar variant, allows for the efficient pooling of global profits and their deployment for debt service or reinvestment, but it also invites greater scrutiny from tax authorities looking to combat base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS).

Mastering the Risk Mitigation Matrix

The third and final pillar is the proactive management of the unique risks inherent in cross-border transactions. A financing structure that looks perfect on a spreadsheet can unravel quickly when exposed to real-world volatility. A robust structure must therefore have built-in mechanisms to defend against these risks.

Key risks and their mitigation strategies include:

- Currency Risk: This is the most obvious and immediate financial risk. A 10% adverse swing in an exchange rate can wipe out a year’s worth of synergies. The primary mitigation tool is hedging. This can be done through currency forward contracts to lock in a future exchange rate, or through options that provide the right, but not the obligation, to exchange currency at a set rate. A more structural approach, as mentioned in Pillar 1, is to finance a portion of the deal in the target’s local currency, creating a natural hedge where local-currency revenues can service local-currency debt.

- Political and Regulatory Risk: This risk encompasses everything from unexpected nationalization to the sudden imposition of capital controls or a regulatory body blocking the deal. Sophisticated acquirers can mitigate this by purchasing political risk insurance, which can cover losses arising from specific government actions. Structuring the investment through a holding company in a country with a strong Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) with the target’s nation can also provide an additional layer of legal protection, granting the investor access to international arbitration in case of disputes.

- Integration and Performance Risk: What if the acquired company fails to perform as expected, making it difficult to service the acquisition debt? This risk can be managed through the financing structure itself. An earn-out, where a portion of the purchase price is contingent on the target meeting certain future performance milestones, is a powerful tool. It reduces the upfront cash requirement and ensures the seller remains motivated. Debt covenants must also be structured with an understanding of the potential for post-merger integration challenges, allowing for enough flexibility or “headroom” so that a temporary dip in performance does not trigger a default.

The Framework in Practice: Lessons from the Titans

Case Study 1: Microsoft’s Acquisition of LinkedIn – The Debt-Fueled Behemoth

Microsoft’s $26.2 billion all-cash acquisition of LinkedIn in 2016 is a masterclass in leveraging a strong balance sheet to execute a large-scale cross-border deal, perfectly illustrating Pillar 1 (Architecting the Capital Stack). Despite holding a massive cash pile, much of it was located offshore. To avoid the significant tax bill associated with repatriating that cash to the United States, Microsoft chose to finance the entire deal with new debt.

The company issued nearly $20 billion in bonds in the U.S. market, taking advantage of historically low interest rates and its pristine AAA credit rating. This decision was strategically brilliant. The cost of the new debt was exceptionally low, and the interest payments were tax-deductible in the U.S., effectively lowering the net cost of financing. This move demonstrated a core principle: even for a cash-rich acquirer, using debt can be a more capital-efficient way to fund a major acquisition, especially when dealing with the tax implications of trapped overseas cash. It was a clean, effective use of senior debt raised in the acquirer’s home market to buy a global asset.

Case Study 2: SoftBank’s Acquisition of ARM – The Global Jurisdictional Play

The 2016 acquisition of UK-based chip designer ARM Holdings by Japan’s SoftBank for $32 billion exemplifies the sophisticated use of Pillar 2 (Solving the Jurisdictional Jigsaw). This was a massive, complex transaction that required a global approach to financing and structuring. SoftBank did not simply use cash from its Japanese operations to buy a UK company.

Instead, SoftBank utilized a multi-layered approach. It drew upon its own vast balance sheet, but also secured a massive bridge loan facility from Japan’s Mizuho Bank. The structure was a testament to global financial engineering, designed to be as efficient as possible. By leveraging its relationships with a major domestic lender, SoftBank secured the necessary firepower quickly. The deal highlighted how a global player can tap its home market’s deep liquidity to execute an ambitious foreign takeover. The complexity also underscored the importance of choosing the right jurisdictions for both raising capital and housing the asset post-acquisition to optimize global cash flows, a core tenet of sophisticated cross-border M&A.

Case Study 3: Walmart’s Acquisition of Flipkart – Hedging Bets in an Emerging Market

Walmart’s $16 billion deal in 2018 to acquire a 77% stake in Indian e-commerce giant Flipkart is a powerful illustration of Pillar 3 (Mastering the Risk Mitigation Matrix) in action. Acquiring a majority stake in a high-growth but not-yet-profitable company in an emerging market like India was fraught with risk, including currency volatility, intense competition, and a complex regulatory environment.

Walmart’s financing structure was designed to manage these risks. The deal was funded with a combination of newly issued debt and cash on hand. By raising a significant portion of its funding in U.S. dollars, Walmart leveraged its access to deep and cheap capital markets. However, it was acutely aware of the Indian rupee currency risk and the operational risks. The deal structure was carefully crafted to navigate India’s stringent foreign direct investment (FDI) regulations. Furthermore, by leaving a significant stake in the hands of existing investors, including co-founder Binny Bansal and other entities, Walmart ensured that local expertise and motivation remained embedded in the company. This approach mitigated integration risk by keeping key stakeholders aligned, a crucial move when entering a market as dynamic and challenging as India. It was a textbook case of balancing a massive financial commitment with prudent risk management.

Conclusion: Is There a “Best” Way to Structure Financing?

Ultimately, the search for a single “best” way to finance a cross-border deal is a fool’s errand. The optimal financing structure is not a one-size-fits-all template but a bespoke solution tailored to the unique circumstances of the deal. It is a carefully calibrated mix that reflects the strategic goals of the acquirer, the nature of the target, the specific jurisdictions involved, and the prevailing global economic climate. The right answer emerges from a rigorous analysis of the three pillars: a well-architected capital stack that balances cost and flexibility, a tax- and legally-efficient jurisdictional structure, and a robust risk mitigation matrix that protects against the inevitable uncertainties of the global market. The most successful M&A professionals are not just dealmakers; they are architects, strategists, and risk managers who understand that how you pay for a deal is just as important as the deal itself. As geopolitical landscapes shift and regulatory scrutiny intensifies, which of these three pillars—Capital Stack, Jurisdictional Jigsaw, or Risk Mitigation—do you believe will become the most critical for M&A professionals to master in the coming decade?

Leave a comment