Beyond the Top Ten: 5 Quantitative Methods to De-Risk Customer Concentration in M&A

In the high-stakes world of mergers and acquisitions, due diligence is our best attempt to turn the unknown into the understood. We scrutinize financial statements, stress-test operating models, and interview management until we are confident we have a clear picture of the asset we are buying. Yet, lurking within an otherwise pristine set of financials can be a sleeper agent of risk, one capable of silently undermining a deal’s entire investment thesis post-close: customer concentration.

An over-reliance on a handful of clients is one of the most common, and potentially devastating, vulnerabilities a target company can possess. The departure of a single, major customer can trigger a cascade of negative effects, instantly eroding revenue, collapsing EBITDA, and leaving the new owner with an asset worth significantly less than the price they just paid. Relying on a simple “top ten customer” list from the data room is no longer sufficient for the sophisticated M&A professional. We need a more rigorous, quantitative framework.

This article provides a deep dive into analyzing and quantifying customer concentration risk. We will first establish the foundational concepts and then explore five distinct quantitative methods that move from basic assessment to a sophisticated, multi-factor view of revenue stability. Our goal is to equip you with a toolkit that transforms the abstract fear of concentration risk into a calculated variable you can manage within your deal-making process.

Setting the Stage: Core Concepts and Modern Realities

Before we dive into the calculations, we must first align on the core principles and the modern context of customer concentration. The nature of this risk is evolving, and our understanding must evolve with it.

Why Customer Concentration is an Existential Threat

The danger of customer concentration is a simple, brutal equation. Imagine acquiring a company for $100 million, based on a 10x multiple of its $10 million in EBITDA. The company’s largest customer, “Goliath Corp,” accounts for 30% of its revenue. Six months after the closing dinner, Goliath Corp is acquired by a competitor and terminates its contract.

Assuming a 40% contribution margin on that lost revenue, the target’s EBITDA does not just dip; it plummets. The 30% revenue loss could easily translate into a 50% or greater drop in profitability. The $10 million EBITDA you acquired is now $5 million. The company you valued at $100 million is now, by the same metric, worth only $50 million. This is the scenario that keeps dealmakers awake at night, and it highlights why a superficial understanding of this risk is inadequate.

Words to Know for a Deeper Analysis

To properly dissect this issue, we need a shared vocabulary:

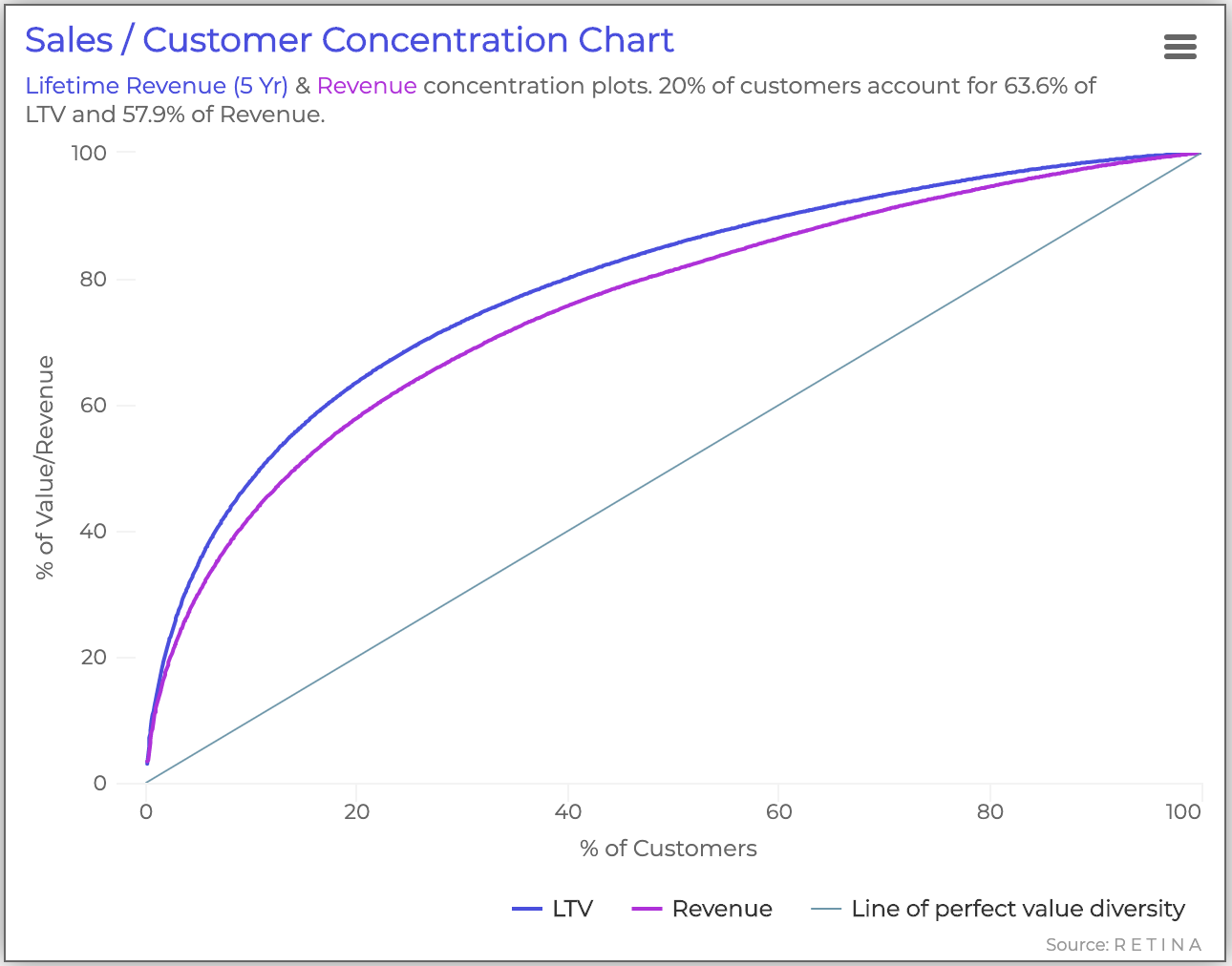

- Customer Concentration: This is the percentage of a company’s total revenue that is derived from a small number of its largest customers. While there is no universal “bad” threshold, a common rule of thumb is that risk becomes notable when a single customer exceeds 10% of revenue, or the top five customers exceed 25%.

- Revenue Stability: This concept goes beyond concentration. It measures the predictability and durability of a company’s revenue streams. A company with high concentration might still have stable revenue if its key customers are locked into long-term, high-switching-cost relationships. Conversely, a company with low concentration could have unstable revenue if it operates on a transactional, project-by-project basis with its entire customer base.

- Customer “Stickiness”: This qualitative-turned-quantitative factor assesses the difficulty or cost for a customer to switch to a competitor. High stickiness can be driven by deep product integration, proprietary technology, unique intellectual property, or simply exceptionally strong, multi-threaded personal relationships.

Current Trends Magnifying the Risk

In today’s globalized economy, several trends are reshaping the landscape of customer concentration. Industry consolidation means that a company’s customers might be merging, creating fewer, more powerful buying entities. The rise of platform economies can also create a new form of concentration, where a business might be critically dependent not on a direct customer, but on a marketplace like Amazon, a platform like the Apple App Store, or a cloud provider like AWS. Understanding these macro trends is essential to place your quantitative analysis in the proper strategic context.

The Quantitative Toolkit: 5 Methods to Assess Revenue Stability

Armed with a clear understanding of the threat, we can now move to quantification. These five methods are best used in concert, as each provides a unique lens through which to view the target’s revenue structure. They range from the straightforward to the complex, allowing for an analysis that is as deep as the available data permits.

The following list presents five powerful methods for your analytical toolkit:

1. The Concentration Ratio (CRn)

This is the most common and straightforward starting point for any concentration analysis. The Concentration Ratio, or CRn, measures the percentage of total revenue generated by the top ‘n’ customers.

- How to Calculate It:

- CRn = (Total Revenue from Top ‘n’ Customers / Total Company Revenue) * 100

- For example, CR1 measures the percentage of revenue from the single largest customer. CR5 measures the percentage from the top five.

- Interpretation and Use: We typically calculate CR1, CR3, CR5, and CR10 to get a tiered view of dependency. A company with a CR1 of 40% presents a fundamentally different risk profile than a company with a CR1 of 8% but a CR10 of 40%. The first is dependent on a single relationship, while the second has a more distributed, albeit still concentrated, top-tier customer base.

- Pros: It is simple to calculate and easy to understand, making it a perfect first-pass metric in early-stage diligence.

- Cons: The choice of ‘n’ is arbitrary. More importantly, it fails to capture the distribution of revenue within the top group. Two companies could have the exact same CR5 of 50%, but one might have a 40% top customer while the other has five customers at 10% each—two vastly different risk profiles that the CRn treats as identical.

2. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)

To overcome the shortcomings of the CRn, we can borrow a tool from antitrust analysis: the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). Instead of measuring market concentration, we will adapt it to measure customer concentration. The HHI provides a more nuanced picture by accounting for the entire customer base and giving exponentially more weight to larger customers.

- How to Calculate It:

- First, express each customer’s revenue as a percentage of total revenue.

- Then, square each customer’s percentage share.

- Finally, sum all the squared figures.

- HHI = Σ (Customer Revenue %)^2

- Interpretation and Use: The HHI scale ranges from near 0 (perfectly distributed) to 10,000 (a single customer represents 100% of revenue). Let’s revisit our CR5 example.

- Company A: CR5 = 50% (Customers at 40%, 4%, 3%, 2%, 1%). HHI = 40² + 4² + 3² + 2² + 1² + … = 1600 + 16 + 9 + 4 + 1 + … ≈ 1630+.

- Company B: CR5 = 50% (Customers at 10%, 10%, 10%, 10%, 10%). HHI = 10² + 10² + 10² + 10² + 10² + … = 100*5 + … = 500+. The HHI clearly distinguishes between the two, assigning a much higher risk score to Company A, as it should. This makes the HHI the discerning analyst’s CRn.

- Pros: It captures the entire distribution of the customer base and accurately reflects the outsized risk of very large customers.

- Cons: It is more data-intensive to calculate. The resulting number (e.g., “1800”) is less intuitive than a simple percentage and often requires benchmarking to be truly meaningful.

3. Customer-Level Cohort Analysis

The CRn and HHI provide a static snapshot in time. To understand the true stability of revenue, we must analyze its dynamics. Cohort analysis, a staple of SaaS and subscription business valuation, can be brilliantly applied to almost any business model where historical transactional data is available.

- How to Calculate It:

- Group customers into cohorts based on the year (or quarter) they first did business with the company.

- Track the revenue generated by each cohort over subsequent years.

- From this, you can calculate key metrics like Net Revenue Retention (NRR), which is (Starting Revenue + Expansion – Churn – Contraction) / Starting Revenue.

- Interpretation and Use: A cohort analysis tells a story. Are customers spending more over time (positive NRR)? Or are they slowly attriting? A target with high concentration but an NRR of 120% from its key accounts is far more attractive than a target with moderate concentration and an NRR of 85%. This analysis directly measures customer “stickiness” and satisfaction in the most objective way possible: with their wallets. It helps answer whether the large customers are a source of stable, growing annuities or melting ice cubes.

- Pros: It is a dynamic, forward-looking indicator of customer health and revenue stability. It is one of the most powerful tools for validating the quality of revenue.

- Cons: It requires clean, detailed, and historical customer-level revenue data, which can be a significant ask during due diligence, especially for smaller or less sophisticated target companies.

4. Scenario Analysis and Impact Quantification

This method bridges the gap between identifying a risk and pricing it into the deal. Here, we move from analyzing concentration to modeling the financial impact of its materialization.

- How to Calculate It: This is a multi-step modeling exercise.

- Identify Key Risk Customers: Use the CRn and HHI to identify the customers that pose the most significant concentration risk.

- Assign Churn Probabilities: This is where qualitative diligence meets quantitative analysis. For each key customer, assign a probability of churn within the next 1-3 years. This probability should be informed by factors like contract length, stated renewal intentions, level of integration, and the health of the relationship. For example, a customer on a month-to-month contract with a new procurement head might get a 25% churn probability, while one on a 5-year auto-renewing contract deeply integrated into their ERP system might get a 2% probability.

- Model the Financial Impact: For each customer, calculate the potential EBITDA loss: Expected EBITDA Loss = (Customer Revenue * Contribution Margin) * Churn Probability.

- Calculate Total Expected Loss: Sum the expected EBITDA loss across all key customers to arrive at a total risk-adjusted EBITDA figure.

- Interpretation and Use: This analysis gives you a dollar amount to anchor negotiations. If your analysis shows a total expected EBITDA loss of $1 million, you can now argue for a purchase price reduction of $10 million (assuming a 10x multiple). Alternatively, it can be used to structure an earn-out, where a portion of the purchase price is contingent on retaining that specific customer revenue for a set period.

- Pros: It directly translates an abstract risk into a concrete financial impact, making it highly actionable for valuation and deal structuring.

- Cons: The assigned churn probabilities are inherently subjective and can be a point of contention between buyer and seller. However, the exercise of debating and defending those assumptions is itself a valuable part of due diligence.

5. The Revenue Stability Index (RSI)

Our final method is the most advanced, creating a composite “index” that blends multiple quantitative and qualitative factors into a single, benchmarkable score. This is your custom-built metric for a holistic view.

- How to Calculate It:

- You design an index by selecting several key factors and assigning them a weight based on their importance. The formula could look something like this:

- RSI = (w1 * HHI_Score) + (w2 * NRR_Score) + (w3 * Avg_Contract_Length_Score) + (w4 * Customer_Diversification_Score)

- Each component is scored on a normalized scale (e.g., 1-100). The HHI_Score would be an inverted score (lower HHI = higher score). The NRR_Score would be based on the cohort analysis. Avg_Contract_Length is self- explanatory. Customer_Diversification_Score could measure how many different industries the top customers operate in.

- Interpretation and Use: The absolute RSI number is less important than its relative value. You can calculate the RSI for the target company and then compare it to other companies in your portfolio or to industry benchmarks you develop over time. This allows you to say, “This target has an RSI of 65, which is 15 points below our average portfolio company at acquisition. This highlights a material risk we need to mitigate or price in.”

- Pros: It provides a comprehensive, 360-degree view of revenue stability in a single metric, perfect for comparing different investment opportunities.

- Cons: It is the most complex method to implement. It requires significant data, and the weighting of the components is subjective and must be based on a well-reasoned investment philosophy.

From Analysis to Action: Mitigating Concentration Risk

Identifying and quantifying risk is only half the battle. The ultimate goal is to mitigate it. Can you reduce the risk to zero? Almost never, especially pre-close. However, you can actively manage it.

- Pre-Close Mitigation: Your analysis from the methods above can directly inform deal structure. Use scenario analysis to justify a lower valuation multiple, a specific indemnity for the loss of a key customer, or an earn-out tied directly to the retention and growth of the top five clients.

- Post-Close Mitigation: This is where the real work begins. The new owner must immediately implement a strategy to de-risk the customer base. This includes launching a charm offensive with key account management for top customers, incentivizing the sales team to land new logos rather than just farm existing accounts, and exploring product or service expansion to sell more diverse offerings to a wider range of clients.

The Canary in the Coal Mine: Early Warning Signs

Once you own the company, you must remain vigilant. Your diligence file should not gather dust; it should be an active risk management playbook. Monitor for early warning signs that a key customer relationship might be souring. These can include a decline in order frequency, a slowdown in payment cycles, turnover of your key contacts within the customer’s organization, or negative news about the customer’s own financial health or industry. When you see these signs, you must act decisively. Proactive engagement, offering new value, and having a contingency plan in place are the hallmarks of a savvy owner.

Conclusion

Analyzing customer concentration risk is not a box-ticking exercise; it is a critical component of a robust M&A diligence process. Moving beyond a simple CRn list and employing a multi-faceted quantitative approach—using tools like the HHI, cohort analysis, scenario modeling, and even a custom Revenue Stability Index—empowers you to truly understand the asset you are buying. It allows you to transform a vague sense of unease into a quantified risk that can be priced, negotiated, and managed.

Ultimately, the best analysis combines these quantitative methods with deep qualitative judgment. The numbers tell you what the risk is, but only conversations with management and customers can tell you why it exists and how “sticky” those relationships truly are. By integrating both, you can make more informed investment decisions and protect your returns from this all-too-common threat. As you reflect on your own processes, what qualitative signals or non-obvious data points have you found most telling when assessing the true “stickiness” of a key customer relationship during due diligence?

Leave a comment